A Critical Review of the Literature

Headache. 2013;53(3):459-473.

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Contexts.—An evidence base for complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) consumption within general populations is emerging. However, research data on CAM use for headache disorders remain poorly documented. This paper, constituting the first critical review of literature on this topic, provides a synopsis and evaluation of the research findings on CAM use among patients with headache and migraine.

Methods.—A comprehensive search of literature from 2000 to 2011 in CINAHL, MEDLINE, AMED, and Health Sources was conducted. The search was confined to peer-reviewed articles published in English reporting empirical research findings of CAM use among people with primary headache or migraine.

Results.—The review highlights a substantial level of CAM use among people with headache and migraine. There is also evidence of many headache and migraine sufferers using CAM concurrent to their conventional medicine use. Overall, the existing studies have been methodologically weak and there is a need for further rigorous research employing mixed method designs and utilizing large national samples.

Discussion.—The critical review highlights the substantial prevalence of CAM use among people with headache and migraine as a significant health care delivery issue, and health care professionals should be prepared to inquire and discuss possible CAM use with their patients during consultations. Health care providers should also pay attention to the possible adverse effects of CAM or interactions between CAM and conventional medical treatments among headache and migraine patients.

Introduction

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) – a diverse group of health care practices and products not traditionally associated with the medical profession or medical curriculum [1] – has increasingly become a mainstream health care activity in Western societies. [2–6] In recent years, CAM has become an issue of growing importance for health care practitioners as well as policy makers. [1,7,8]

Over recent decades, an evidence base for CAM consumption within general populations has emerged. [9–13] However, research data on CAM use for specific health or clinical conditions remain less well documented, and the use of CAM specifically for headache and migraine is no exception. This paper provides the first critical, systematic examination of the evidence base of this crucial health care issue, synthesizing empirical research findings and highlighting a number of gaps and challenges facing future research in this increasingly important practice area.

Headache and Migraine: The Significance of Exploring CAM Use

Headache and migraine is a very common health condition, and according to the International Headache Society, the percentage of the global adult population with an active general headache disorder is 46%, with 11% suffering from migraines, 42% suffering tension-type headaches, and 3% suffering chronic daily headache. [14] A systematic review has identified the global prevalence of chronic migraine at 0–5.1%, with estimates typically in the range of 1.4–2.2% of the general population. [15] The impact of headache disorders is substantial, and the World Health Organization ranks headache disorders as some of the most disabling conditions for both men and women. [14] Given the substantial effect of headache and migraine on the quality of life of the sufferer and the significant disruption to work, family, and social duties, [16–18] it is imperative that all effective headache and migraine treatments be explored and researched.

Conventional medical intervention for headache and migraine often involves pharmacological treatment. Acetaminophen (paracetamol), acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), dipyrone, derivatives of ergot fungus, chlorpromazine, triptans (Imitrex/Imigran, et al), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories are the most commonly prescribed drugs for the acute treatment of headache and migraine. [19] Tricyclic antidepressants, β-blockers, and anti-epilepsy drugs are the most commonly prescribed and best evidence-based classes of pharmacologic preventative interventions for episodic migraine. [20] Despite many patients reporting benefits from these drug treatments, the pharmacological interventions are not without their limitations or side effects. For instance, amitriptyline, one of the most widely used preventive antimigraine agents, has side effects ranging from drowsiness, dry mouth, constipation, and weight gain to the possibility of precipitating cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, or exacerbating closed-angle glaucoma. [19] In addition, headache and migraine are often long term, with relapses and remissions that create continuing distress and disruption to patients’ daily lives. [16]

The treatment of headache and migraine is one area of health care where CAM treatment shows some promise. [21–28] Nevertheless, the benefits and risks of CAM in treating and managing headache and migraine disorders remain contested, and a recent systematic assessment of the evidence base of CAM treatment for primary headache found that the overall quality of research of CAM approaches still lags behind studies of conventional medical approaches to primary headache. [29]

Results from large cohort/population studies suggest that CAM use is common among headache and migraine patients. For instance, a US study on symptoms and conditions among CAM users in a large military cohort (n = 86,131) suggested that about 10% of the respondents reported the problem of migraine headache and the study suggested this condition is more likely to be reported by CAM users than by people not using CAM. [30] Analysis of the US National Health Interview Survey (n = 31,044) also identified headache as one of the most common health problems experienced by CAM users. [31] While these studies highlight a relationship between CAM use and headache disorders, they provided little information on the patterns of and motivations for CAM use among people with headache and migraine.

Although evidence of CAM use for headache and migraine is emerging, there has been no review or synthesis of CAM user characteristics, perceptions, or motivations among headache and migraine sufferers. Such a review is essential in order to provide important insights for health practitioners and policy-makers with regard to the safety and continuity of care for patients – an issue pronounced by the fact that CAM users appear not to disclose such use to their conventional doctors. Previous studies reveal that a lack of general practitioner (GP) interest in their patients’ use of CAM or the patients’ perception that CAM use is not an important issue that should be raised with their doctor are the 2 major factors contributing to nondisclosure of CAM. [32–34] In response, this paper provides the first synopsis and evaluation of the research findings on CAM use among patients with headache and migraine as identified from recent international empirical literature. Specifically, this paper aims to: (1) identify the relevant studies that examine the use of CAM among people with headaches; (2) analyze the quality of these studies; and (3) summarize the key findings from these studies using theme-based analysis.

Methods

Design

The aim of the review is to examine the current prevalence, pattern, and details of CAM use among people with headache and migraine. A comprehensive search of the literature between 2000 and 2011 was undertaken in line with the exponential growth in CAM use and growing research attention upon this topic over the past decade. The CINAHL, MEDLINE, Health Source, and AMED databases were searched, using the following key terms and phrases: complementary medicine/therapy, alternative medicine/therapy, natural medicine/therapy, holistic medicine/therapy, headache, primary headache, migraine, cephalalgia, cephalgia, cranial pain, and hemicrania. The CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Health Source are 3 of the most popular, comprehensive databases for health and medicine scholarship. The AMED database was also chosen as an authoritative resource on allied health and complementary medicine scholarship. The database search was confined to peer-reviewed articles published in English.

To ensure all relevant international literature was identified, the authors also conducted hand searches in prominent headache and migraine journals including Headache, Cephalalgia, and Journal of Headache and Pain. Relevant works were also identified by examining bibliographies of publications.

The search results were imported into Endnote, [35] a bibliographic management system software program, with all duplicated items removed. The remaining titles and their abstracts were screened and assessed independently by 2 authors who employed the following criteria to identify relevant studies for inclusion in the review: Peer-reviewed, research-based papers reporting new empirical findings focusing upon either CAM use among people with primary headache or migraine, or CAM use among a broader population or general population where CAM use among headache and/or migraine patients was clearly identifiable and extractable.

Those papers identified as individual case reports or CAM clinical trials were excluded from the review. In those circumstances where the abstract was deemed to not provide sufficient information, the full article was retrieved and examined prior to a final decision regarding inclusion or exclusion status.

Search Outcomes

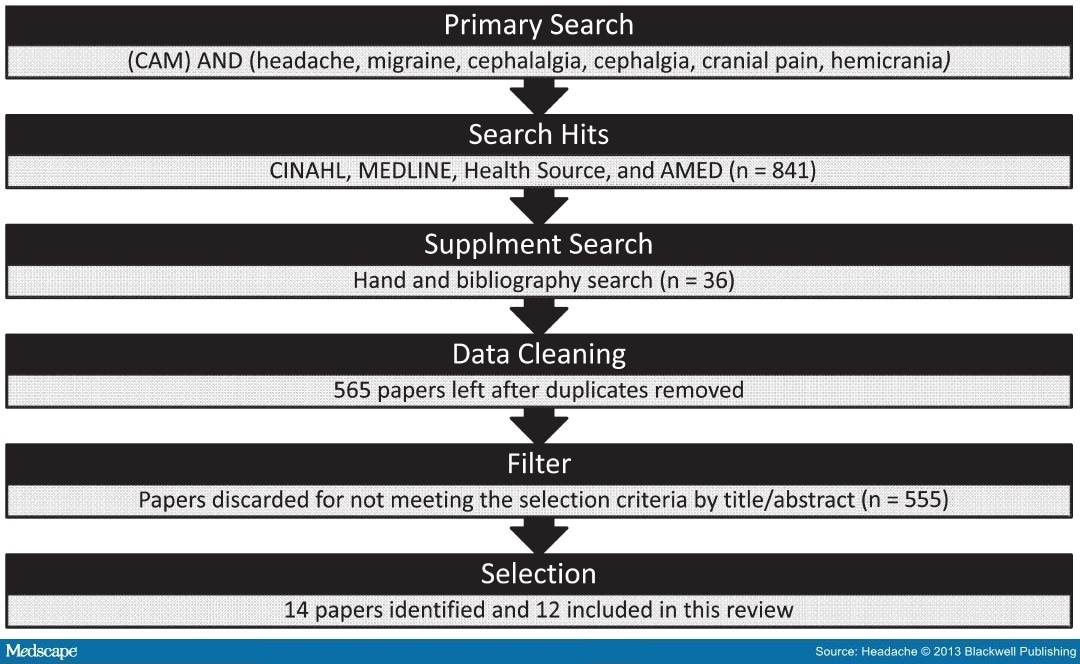

The initial search identified 565 papers, and a total of 14 articles met the selection criteria. Two of these 14 articles [36,37] were subsequently eliminated due to the reporting of the findings of surveys that were already covered elsewhere. [38,39] As a result, a total of 12 papers were included in this review. The Figure reports the literature search process, and summarizes the basic details of the included papers.

Table 1. Research-Based Studies on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) for Headache and Migraine, 2000–2011

| Author/Country | Design/Sampling | Use Rate | Popular Therapies Used | Predictors of Use | Special Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eisenberg et al,40 USA | Survey of adults who saw a medical doctor and used CAM therapies National representative sample, n = 831 |

NA | NA | NA | Study on the general |

| Population Gaul et al, 38 Austria and Germany | Survey of patients of 7 tertiary headache centers Convenience sample, n = 432 |

81.7% used at least 1 CAM (lifetime use) for headache therapy 71.1% used CAM in addition to conventional treatment for headache Median CAM therapies used for headache = 3.9 during the course of disease Mean duration of CAM use for headache = 7.2 years |

Acupuncture (58%) Massage (46%) Relaxation techniques (42%) Homeopathy (23%) |

A higher number of headache days† Longer duration of headache treatment† Higher personal costs† Use of CAM for other diseases† |

Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Kozak et al, 41Switzerland | Survey of outpatients of a headache and pain clinic Convenience sample, n = 1625 |

29.8% reported use of CAM treatments before and after referral to the clinic | Acupuncture (69.8%) Homeopathy (24.8%) |

NA | Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Lambert et al,42 UK | Survey of patients attending an outpatient headache clinic Convenience sample, n = 92 |

32% used a median of 3 CAM therapies for headache (lifetime use) 46% used CAM for headache had also used it for other conditions (lifetime use) |

Massage (15%) Acupuncture (13%) Herbal medicine (12%) Exercise (11%) Vitamins/supplements (10%) |

Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) score in the range of 42–60 and 61–78 | Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Metcalfe et al,43 Canada | A community health survey of people aged ≥12 National representative sample, n = 400,055 |

19.0% of people with migraine visited a CAM practitioner (in last 12 months) People with migraine had a significantly higher odds of using CAM (OR = 1.78) |

People with migraine had significantly higher odds in using chiropractic service (OR = 1.48) and massage therapist (OR = 1.13) than the general population | Migraine remained significant predictors (OR = 1.42) of CAM use after controlling for demographic factors | Study on the general population |

| Rossi et al, 44Italy | Interview of patients, 16–65 years, of a headache clinic with different migraine subtypes Convenience sample, n = 481 |

31% – used for migraine (in the past) 17% – used for migraine (in last 12 months) 69% – never used for migraine 89% CAM users – used specifically for headache Median CAM therapies used for migraine = 1 |

Acupuncture (27%) Homeopathy (22%) Massage (10%) Chiropractic (9%) |

A diagnosis of medication overuse + migraine without aura and chronic migraine Higher number of specialist consults Higher number of conventional GP consults Comorbid psychiatric disorders Higher annual household income Headache either misdiagnosed or not diagnosed |

Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Rossi et al, 45 | Italy Interview of patients, 18–65 years, of a headache clinic suffering from CTTHs Convenience sample, n = 110 |

40% – used for CTTH (in the past) 23% – used for CTTH (in last 12 months) 60% – never used for CTTH |

Chiropractic (22%) Acupuncture (18%) Massage (18%) Homeopathy (8%) |

Higher number of lifetime conventional GP consults Comorbid psychiatric disorders Higher annual household income Had never used pharmacological preventative therapy |

Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Rossi et al, 46Italy | Interview of patients, 18–65 years, of a headache clinic suffering from CHs Convenience sample, n = 100 |

29% – used for CH (in the past) 10% – used for CH (in last 12 months) 71% – never used for CH |

Acupuncture (30%) Homeopathy (14%) Acupressure (12%) Chiropractic (12%) Therapeutic touch (10%) |

Higher number of lifetime conventional GP consults Higher number of cluster headache per year |

Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Soon et al, 47Singapore | Surveys at baseline and 3 months interval of patients of a specialist headache clinic Convenience sample, n = 38 |

34% reported use after consult with GP 18% reported use after consult with specialist |

31% – traditional medicine (the most widely used therapies at baseline) 11% – acupuncture (the most widely used therapies at 3 months interval) |

NA | Study on people with headache and migraine |

| von Peter et al,48 USA | Interview of patients, 18 years and older, with headache syndromes attending a head and neck pain clinic Convenience sample, n = 73 |

84% used ≥1 treatments for headache, with a mean amount of 3 ± 2 modalities used per patient (lifetime use) A mean knowledge of 7 ± 9 treatments per patient |

Massage (42%) Exercise (30%) Acupuncture (19%) Biofeedback (15%) Chiropractic (15%) Herbs (15%) Vitamins/supplements (14%) Therapeutic touch (10%) |

NA | Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Vukovic et al, 49Croatia | Survey of adults >18 years oldConvenience sample, n = 616,115 with M 327 with TTH 174 with PM and TTH |

27% of M, 27% of TTH, and 28% of PM patients used CAM (lifetime use) | For M patients: Physical therapy (10%) Acupuncture (9%) Yoga, meditation (7%) For TTH patients: Physical therapy (12%) Chiropractics (4%) Acupuncture/yoga, meditation (3%) For PM patients: Physical therapy (10%) Chiropractics (7%) Acupuncture (5%) |

NA | Study on the general population |

| Wells et al, 39USA | Secondary analysis of a national health survey Representative sample, n = 23,393 |

50% of adults with migraines or severe headaches used at least 1 CAM (in last 12 months), compared with 34% of those without migraines or severe headaches; adjusted OR = 1.29 with 95% CI | Mind–body therapies (including deep breathing exercises, meditation, yoga, progressive relaxation, guided imagery) were used most frequently among adults with migraines or severe headaches (30%) | Higher educational attainment, a history of anxiety, joint or low back pain, light or heavy alcohol use, and living in the western USA | Study on people with headache and migraine |

†Predictors for a higher number of used CAM treatments.

CTTH = chronic tension-type headaches; CH = cluster headaches; CI = confidence interval; GP = general practitioner; M = migraine; NA = not applicable; OR = odds ratio; PM = probable migraine; TTH = tension-type headache.

Figure.

Flowchart of literature search process. CAM = complementary and alternative medicine.

Quality Appraisal

In order to appraise the quality of the papers identified for review, the authors employed a quality scoring system () drawing upon quality assessment tools previously used for assessing prevalence studies on low back pain [50] and CAM use among cancer patients. [51,52]The use of these established analytical tools allowed for systematic comparison and evaluation of the CAM surveys reviewed.

Table 2. Description of Quality Scoring System for the Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Surveys Reviewed (Sources: Adapted From Fejer et al 50 and Bishop et al 51,52)

| Dimensions of Quality Assessment | Points Awarded† |

|---|---|

| Methodology |

|

| A. Representative sampling strategy | 1 |

| B. Sample size >500 | 1 |

| C. Response rate >75% | 1 |

| D. Low recall bias (prospective data collection or retrospective data collection within past 12 months) | 1 |

| Reporting of participants’ characteristics |

|

| E. Types of headache/migraine | 1 |

| F. Age | 1 |

| G.Ethnicity | 1 |

| H. Indicator of socioeconomic status (eg, income, education) | 1 |

| Reporting of CAM use |

|

| I. Definition of CAM or modalities provided to participants | 1 |

| J. Participants can name CAM therapies/modalities used (open question) | 1 |

| K. Use of CAM modalities assessed | 1 |

†Maximum score: 11 points.

Two authors assigned scores to the studies separately; the results were then compared and disagreements and differences resolved by discussion. reports the quality score of each individual study.

Table 3. Quality Score of Studies on Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Use Among Headache and Migraine Patients†

| Authors/Year | Dimensions of Quality Assessment | Total Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methodology | Reporting of Participants’ Characteristics | Reporting of CAM Use | ||

| Gaul et al (2009) 38 | 1 (C) | 3 (E,F,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 7 |

| Kozak et al (2005) 41 | 2 (B,C) | 3 (E,F,H) | 1 (I) | 6 |

| Lambert et al (2010) 42 | 1 (C) | 3 (F,G,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 7 |

| Rossi et al (2005) 44 | 0 | 3 (E,F,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 6 |

| Rossi et al (2006) 45 | 0 | 3 (E,F,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 6 |

| Rossi et al (2008) 46 | 0 | 3 (E,F,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 6 |

| von Peter et al (2002) 48 | 0 | 4 (E,F,G,H) | 2 (I,K) | 6 |

| Wells et al (2011) 39 | 3 (A,B,D) | 3 (F,G,H) | 2 (I,K) | 8 |

†Eisenberg et al, 40 Metcalfe et al, 43 Soon et al, 47 and Vukovic et al 49 do not focus solely upon CAM use for headache and migraine and, as such, the criteria “reporting of CAM use” does not apply to these 4 studies and they were not assessed via the quality scoring system mentioned.

Results

The context and findings of the 12 papers were extracted, grouped, and summarized using an integrative review approach. [53,54] The data extracted were synthesized using the following themes: the prevalence of CAM use, user profile and predictors of use, motivation and perception of CAM use, and referral and disclosure of CAM use.

The Prevalence of CAM Use

The 12 papers selected for review reported a wide range of prevalence rates for CAM use among people with headache and migraine (refer to ). For instance, an analysis of national health survey data identified 50% of US adults with migraines or severe headaches as using at least one CAM over the past 12-month period. [39] A similar analysis in Canada discovered that 19% of people with migraine visited a CAM practitioner in the last 12 months. [43] A large cross-sectional cohort study among patients of tertiary headache centers in Austria and Germany found that 82% of the respondents had used CAM at some stage in their lifetime. [38] Three studies conducted in Italy on patients with different types of headache disorders reported CAM use rates of 31% (among patients with migraine), 40% (among patients with chronic tension-type headaches), and 29% (among patients with cluster headaches). [44–46] Meanwhile, another survey of adults in Croatia identified 28% of respondents with headache disorders had used CAM (lifetime prevalence). [49] Despite these variations in findings, the studies do indicate relatively substantial prevalence of CAM use among people suffering from headache and migraine.

Table 1. Research-Based Studies on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) for Headache and Migraine, 2000–2011

| Author/Country | Design/Sampling | Use Rate | Popular Therapies Used | Predictors of Use | Special Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eisenberg et al,40 USA | Survey of adults who saw a medical doctor and used CAM therapies National representative sample, n = 831 |

NA | NA | NA | Study on the general |

| Population Gaul et al, 38 Austria and Germany | Survey of patients of 7 tertiary headache centers Convenience sample, n = 432 |

81.7% used at least 1 CAM (lifetime use) for headache therapy 71.1% used CAM in addition to conventional treatment for headache Median CAM therapies used for headache = 3.9 during the course of disease Mean duration of CAM use for headache = 7.2 years |

Acupuncture (58%) Massage (46%) Relaxation techniques (42%) Homeopathy (23%) |

A higher number of headache days† Longer duration of headache treatment† Higher personal costs† Use of CAM for other diseases† |

Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Kozak et al, 41Switzerland | Survey of outpatients of a headache and pain clinic Convenience sample, n = 1625 |

29.8% reported use of CAM treatments before and after referral to the clinic | Acupuncture (69.8%) Homeopathy (24.8%) |

NA | Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Lambert et al,42 UK | Survey of patients attending an outpatient headache clinic Convenience sample, n = 92 |

32% used a median of 3 CAM therapies for headache (lifetime use) 46% used CAM for headache had also used it for other conditions (lifetime use) |

Massage (15%) Acupuncture (13%) Herbal medicine (12%) Exercise (11%) Vitamins/supplements (10%) |

Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) score in the range of 42–60 and 61–78 | Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Metcalfe et al,43 Canada | A community health survey of people aged ≥12 National representative sample, n = 400,055 |

19.0% of people with migraine visited a CAM practitioner (in last 12 months) People with migraine had a significantly higher odds of using CAM (OR = 1.78) |

People with migraine had significantly higher odds in using chiropractic service (OR = 1.48) and massage therapist (OR = 1.13) than the general population | Migraine remained significant predictors (OR = 1.42) of CAM use after controlling for demographic factors | Study on the general population |

| Rossi et al, 44Italy | Interview of patients, 16–65 years, of a headache clinic with different migraine subtypes Convenience sample, n = 481 |

31% – used for migraine (in the past) 17% – used for migraine (in last 12 months) 69% – never used for migraine 89% CAM users – used specifically for headache Median CAM therapies used for migraine = 1 |

Acupuncture (27%) Homeopathy (22%) Massage (10%) Chiropractic (9%) |

A diagnosis of medication overuse + migraine without aura and chronic migraine Higher number of specialist consults Higher number of conventional GP consults Comorbid psychiatric disorders Higher annual household income Headache either misdiagnosed or not diagnosed |

Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Rossi et al, 45 | Italy Interview of patients, 18–65 years, of a headache clinic suffering from CTTHs Convenience sample, n = 110 |

40% – used for CTTH (in the past) 23% – used for CTTH (in last 12 months) 60% – never used for CTTH |

Chiropractic (22%) Acupuncture (18%) Massage (18%) Homeopathy (8%) |

Higher number of lifetime conventional GP consults Comorbid psychiatric disorders Higher annual household income Had never used pharmacological preventative therapy |

Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Rossi et al, 46Italy | Interview of patients, 18–65 years, of a headache clinic suffering from CHs Convenience sample, n = 100 |

29% – used for CH (in the past) 10% – used for CH (in last 12 months) 71% – never used for CH |

Acupuncture (30%) Homeopathy (14%) Acupressure (12%) Chiropractic (12%) Therapeutic touch (10%) |

Higher number of lifetime conventional GP consults Higher number of cluster headache per year |

Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Soon et al, 47Singapore | Surveys at baseline and 3 months interval of patients of a specialist headache clinic Convenience sample, n = 38 |

34% reported use after consult with GP 18% reported use after consult with specialist |

31% – traditional medicine (the most widely used therapies at baseline) 11% – acupuncture (the most widely used therapies at 3 months interval) |

NA | Study on people with headache and migraine |

| von Peter et al,48 USA | Interview of patients, 18 years and older, with headache syndromes attending a head and neck pain clinic Convenience sample, n = 73 |

84% used ≥1 treatments for headache, with a mean amount of 3 ± 2 modalities used per patient (lifetime use) A mean knowledge of 7 ± 9 treatments per patient |

Massage (42%) Exercise (30%) Acupuncture (19%) Biofeedback (15%) Chiropractic (15%) Herbs (15%) Vitamins/supplements (14%) Therapeutic touch (10%) |

NA | Study on people with headache and migraine |

| Vukovic et al, 49Croatia | Survey of adults >18 years oldConvenience sample, n = 616,115 with M 327 with TTH 174 with PM and TTH |

27% of M, 27% of TTH, and 28% of PM patients used CAM (lifetime use) | For M patients: Physical therapy (10%) Acupuncture (9%) Yoga, meditation (7%) For TTH patients: Physical therapy (12%) Chiropractics (4%) Acupuncture/yoga, meditation (3%) For PM patients: Physical therapy (10%) Chiropractics (7%) Acupuncture (5%) |

NA | Study on the general population |

| Wells et al, 39USA | Secondary analysis of a national health survey Representative sample, n = 23,393 |

50% of adults with migraines or severe headaches used at least 1 CAM (in last 12 months), compared with 34% of those without migraines or severe headaches; adjusted OR = 1.29 with 95% CI | Mind–body therapies (including deep breathing exercises, meditation, yoga, progressive relaxation, guided imagery) were used most frequently among adults with migraines or severe headaches (30%) | Higher educational attainment, a history of anxiety, joint or low back pain, light or heavy alcohol use, and living in the western USA | Study on people with headache and migraine |

†Predictors for a higher number of used CAM treatments.

CTTH = chronic tension-type headaches; CH = cluster headaches; CI = confidence interval; GP = general practitioner; M = migraine; NA = not applicable; OR = odds ratio; PM = probable migraine; TTH = tension-type headache.

There are several factors that may account for the differences in reported prevalence of CAM use. First of all, the differences may reflect variations in study or sample design with different studies targeting different populations or types of headache/migraine patients. For instance, patients in the general population may be different from patients presenting in headache-specific clinics. In addition, studies have adopted different definitions of CAM which may also contribute to the differences in reported prevalence rates. For example, Rossi et al [44] defined CAM as “a wide range of pharmaceutical-type and non-pharmacological therapies that do not, on the whole, fall within the sphere of conventional medicine.” In contrast, Lambert et al [42] adopt a definition of CAM in their study that was “essentially respondent-defined,” and Metcalfe et al [43] confined their analysis of CAM use to visits to CAM practitioners. Finally, the variation in ways of measuring CAM use (eg, lifetime use or use in the past year) is another factor that renders the interpretation and comparison of prevalence estimates between studies of a particular challenge.

Acupuncture, massage, chiropractic, and homeopathy were the most common therapies reported as used by those suffering from headache and migraine in the studies reviewed. The findings of a large national representative survey suggested that mind–body therapies such as meditation, breathing exercise, and yoga were the most common CAM used by US respondents with migraines or severe headaches. [39] There is evidence that a majority of CAM users seek CAM concurrent with (ranged from 7% to 30%) or following (ranged from 64% to 93%) a GP visit. [42,44–46] In contrast, only a small proportion of respondents (ranging from 5% to 19%) used CAM before they visited a doctor. [42,44–46] Lambert et al [42] also found that 80% of their study respondents did not relinquish their use of prescribed medications while consuming CAM. Together, these results suggest that CAM is likely used as a complementary (alongside) rather than an alternative treatment (as a replacement) to conventional medicine among people with headache and migraine.

CAM User Profile and Predictors of CAM Use

The sociodemographic characteristics of headache and migraine sufferers who use CAM are similar to the profile of CAM users identified in the general population. [9,12] Specifically, people with headache and migraine who use CAM are more likely to be female,[38,39,42,44–48] be married, [44–46,48] have a higher education level, [38,39,42,44–46,48] report a higher annual income, [38,39,44–46] and be full-time employed. [42,44–47]

Research evidence indicates that the seriousness of headache conditions (in terms of number of headache days, duration of headache treatment, or frequency of GP/specialist consulted) is an important factor that determines CAM consumption; people with more severe headache conditions are more likely to use CAM. [38,43–46] Lambert et al [42] also found that a Headache Impact Test score − a widely used tool to measure the impact of headaches on a person’s ability to function on the job, at home, at school, and in social situations − is of significance as a predictor of CAM use. In addition, analysis of data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey indicates that other health conditions or lifestyle characteristics such as a history of anxiety, joint or low back pain, and alcohol use are independently associated with higher CAM use among patients with migraines or severe headaches. [39]

Motivations for and Perceptions of CAM Use

summarizes the findings regarding motivations and perceptions of CAM use from the 12 studies selected for review. Wells et al [39] identified that headache and migraine patients who employed CAM perceived conventional treatment as ineffective more often than those who did not use CAM, and a national representative survey in the USA revealed that 39% of those people who consulted a doctor and used CAM considered CAM as more effective than conventional medicine in treating headache. [41] However, findings from other studies indicate that only a small portion of headache and migraine patients sought CAM in response to a bad experience or dissatisfaction with their conventional treatment. [38,42,44–46]

Table 4. Motivation, Perception, and Referral/Disclosure of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Use for Headache and Migraine

| Author/Country | Motivation for Use | Perception of Use | Referral/Disclosure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eisenberg et al, 40USA | NA | 39% – CAM to be more helpful than conventional medicine for treatment of headache | NA |

| Gaul et al, 38Austria and Germany | 64% – “to leave nothing undone” 56% – “to be active against the disease” 40% – “not to take a permanent medication” 39% – “advice from another person” 34% – “dissatisfaction from conventional treatment” 31% – “request for a therapy without side effects” 20% – “anxiety of side effects” 9% – “bad experience with regular treatments” 8% – other |

NA | NA |

| Lambert et al, 42UK | 48% – as a last resort 21% – believed it was effective 17% – unhappy with conventional treatment 14% – GP recommendation |

60% – found therapy greatly reduced/reduced headache 40% – found therapy had no effect on headache 58% – satisfied/very satisfied with therapy 35% – dissatisfied/very dissatisfied with therapy 0% – made headache worse |

Referral: 72% – friend/relative 16% – GP 8% – nurse 4% – self-recommendation Disclosure: 58% – informed GP/nurse 42% – did not inform GP/nurse |

| Rossi et al, 44 Italy | 48% – potential benefit 27% – safer and less side effects 11% – GP recommendation 10% – proven beneficial for headache 5% – dissatisfied with conventional treatment |

40% – effective 57% – ineffective 4% – made condition worse |

Referral: 53% – friends/relatives 34% – doctor 13% – self-recommendation Disclosure : 39% – informed GP 61% – did not inform GP |

| Rossi et al, 45 Italy | 45% – potential benefit 27% – safer and less side effects 18% – GP recommendation 9% – dissatisfied with conventional treatment |

41% – effective 59% – ineffective |

Referral: 41% – friends/relatives 34% – GP 25% – self-recommendation Disclosure: 40% – disclosed to GP 60% – did not disclose to GP |

| Rossi et al, 46 Italy | 45% – potential benefit 28% – safer and less side effects 14% – GP recommendation 10% – holistic approach to health 5% – dissatisfied with conventional treatment |

36% – effective or quite effective 58% – ineffective 6% – made condition worse |

Referral: 54% – friends/relatives 26% – GP 20% – self-recommendation Disclosure: 38% – disclosed to GP 62% – did not disclose to GP |

| Soon et al, 47Singapore | NA | NA | 5% reported informing GP about the use 11% reported informing the specialist about the use |

| von Peter et al, 48USA | NA | 60% – considered therapies used to have a benefit The highest percentage of patients believed in massage (28/8%), acupuncture (28.7%), and meditation (16.4%) for the relief of headache |

NA |

| Vukovic et al, 49Croatia | NA | 39% of M, 60% of TTH, and 41% of PM patients satisfied with CAM | NA |

| Wells et al, 39USA | Main reasons for CAM use: –General wellness/disease prevention –Family/friends recommendation –To improve/enhance energy Only 5% adults with migraines or severe headaches used CAM to specifically treat their headache symptomsAdults with migraines/severe headaches used CAM more often than those without because: –Their provider recommended it (31% vs 23%) –Conventional treatment was ineffective (21% vs 13%) –Conventional treatment was too expensive (11% vs 5%) |

NA | Disclosure: 43% discussed CAM use with health care provider Adults with migraines/severe headaches had a higher disclosure rate (47%) than those without (42%) |

GP = general practitioner; M = migraine; NA = not applicable; TTH = tension-type headache.

The most common reasons for CAM use as identified by Gaul et al [38] were “to leave nothing undone” (64%) and “to be active against the disease” (56%). This study also found that other considerations like “anxiety of side effects [of conventional treatments]” (20%) and “request for a therapy without side effects” (31%) were also important in headache and migraine patients seeking CAM. Lambert et al [42] found that 48% of their respondents chose to use CAM “as a last resort.” The 3 Italian studies by Rossi et al [44–46] identified a belief among patients that CAM was “potentially beneficial for headache” (about 45%) or CAM was “safer and [with] less side effects [than conventional treatments]” (about 27%) as major reasons for CAM use. In contrast, the analysis of the US national health survey data reveals that while nearly half of adults with migraines or severe headaches use CAM, only about 5% of them use CAM to specifically treat their headache/migraine symptoms. Instead, the main reasons of using CAM as reported in this study were “general wellness/disease prevention” and “to improve/enhance energy.” [39]

Previous study findings indicate that perceptions of CAM effectiveness are mixed among headache and migraine patients who are CAM users. Lambert et al [42] explain that 60% of respondents report CAM as reducing/greatly reducing their headache and 58% were satisfied with the therapy used. von Peter et al [48] also found that 60% of the headache patient population interviewed perceived CAM as of potential benefit for the treatment and relief of headache.

However, the 3 surveys conducted by Rossi et al [44–46] reveal that over half of respondents (ranging from 57% to 59%) experienced CAM as ineffective in the treatment of their headache disorders and this was particularly the case among those with migraine (73.1% reporting CAM as being ineffective). [44] In addition, about 5% of respondents in 2 of these Italian studies reported CAM treatment as resulting in a deterioration of their condition. [44,46] Finally, Vukovic et al [49] report that satisfaction with CAM varied among patients suffering from different kinds of headache conditions, with 39% of patients with migraine, 60% of patients with tension-type headache, and 41% of patients with probable migraine and tension-type headache reporting satisfaction with their CAM treatment.

Referral to and Disclosure of CAM Use

A review of the research literature identifies 3 key sources utilized by people with headache and migraine to gain information about CAM. A substantial proportion of headache and migraine patients using CAM (ranging from 41% to 72%) obtain information about CAM from their acquaintances or relatives. [42,44–46] The patients’ doctor or nurse was the second common referral source through which headache and migraine patients became familiar with CAM (ranging from 16% to 34%) and a relatively small proportion of headache and migraine patients (ranging from 4% to 20%) relied solely upon their own judgment with regard to using these treatments. [42,44–46]

In line with findings from studies of general CAM users, [32] headache and migraine patients utilizing CAM do not commonly inform their doctor or nurse about such CAM use. Wells et al [39] discovered that although CAM users with migraine or headache had a higher disclosure rate than those without migraine or headache, less than half (47%) discuss their CAM use with their conventional health care provider(s). The 3 surveys conducted in Italy by Rossi et al [44–46] identify over 60% of respondents as failing to disclose their CAM use to their conventional doctor. Meanwhile, Soon et al [47] reveal that only 16% of headache and migraine patients in Singapore using CAM informed their doctor or specialist about such use.

In contrast, Lambert et al, [42] examining headache and migraine patients in the UK, report 58% of their respondents as disclosing CAM use to their doctor or nurse. However, the same survey also discovered that 80% of respondents report their doctor or nurse as never inquiring or initiating discussion with them about CAM use. Rossi et al [44] also questioned their respondents about their reasons for failing to inform conventional doctors about their CAM use. In response, 37% of the migraine patients reported that their doctors never ask for this information and 50% of them considered CAM use as a matter either “not important for the doctor to know” or “none of the doctor’s business.”

Discussion

This paper provides the first critical, comprehensive review of the evidence base of CAM use and users among people suffering from headache and migraine. The use of CAM among patients with headache and migraine is an issue that has increasingly attracted the attention of practitioners and researchers over the past decade, [28,55,56] as reflected by the review findings with the bulk of empirical studies (10 out of the 12 studies identified over the last 11 years) having been published since 2005.

Although the evidence base focused upon CAM use among headache and migraine patients has begun to emerge, the ability of this review to generalize from studies or compare findings across studies remains difficult with variations in research design and the definition of CAM employed between studies of particular challenge. This is a problem that also plagues the assessment of clinical outcomes of CAM therapies on treating primary headache. [29] In addition, this review is confined to English language publications and the omission of non-English materials may introduce some bias.

Despite these limitations, the evidence identified and examined in this review does, nevertheless, suggest a substantial level of CAM use among people with headache and migraine. There is also evidence of many headache and migraine sufferers using CAM concurrent to their conventional medicine use (as a complement rather than alternative), a finding consistent with survey results of CAM use in the broader general population. [9,57]

The frequent use of a range of CAM among people with headache and migraine warrants further investigation. There is evidence that many people use CAM as a follow-up treatment or last resort in an attempt to relieve their headache and migraine symptoms. In contrast, recent findings of a large national health survey indicate that only a small proportion of people with migraines and severe headaches use CAM specifically for the treatment of their headache conditions. [39] The coexistence of a high CAM usage with the fact that a substantial proportion of users consider CAM ineffective in treating their headache symptoms is also interesting. [44–46] In short, the role of CAM in treating headache and migraine symptoms or helping patients to cope with their distress in their everyday lives remains unclear. There is a need for further in-depth qualitative studies on the motivations, experiences, and perceptions of CAM use among headache and migraine sufferers.

The prevalence of CAM use among headache and migraine patients also has implications for conventional health care providers. Because the prevalence rate of CAM is high among headache and migraine patients and a substantial percentage of these patients appear to not disclose their CAM use to conventional practitioners, health care professionals should be prepared to inquire and discuss with their patients about possible CAM use. Relevant health care providers should also pay attention to the possible adverse effects of CAM or interactions between CAM and conventional medical treatments among headache and migraine patients. This is important given a very small minority of headache and migraine patients who utilize CAM report deterioration in their condition. [44,46]

In light of this review, it is possible to identify areas for future research attention pertaining to headache and migraine patients and CAM use. As the quality scores reported in indicate, the studies examining this topic to date have been methodologically weak. Only 2 of the studies attracted a sample size over 500, with only one of them employing a nationally representative sample. As such, there is a pressing need for rigorous studies examining this important field of CAM use and user research, employing mixed method designs and utilizing large and/or representative national samples where possible.

Table 3. Quality Score of Studies on Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Use Among Headache and Migraine Patients†

| Authors/Year | Dimensions of Quality Assessment | Total Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methodology | Reporting of Participants’ Characteristics | Reporting of CAM Use | ||

| Gaul et al (2009) 38 | 1 (C) | 3 (E,F,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 7 |

| Kozak et al (2005) 41 | 2 (B,C) | 3 (E,F,H) | 1 (I) | 6 |

| Lambert et al (2010) 42 | 1 (C) | 3 (F,G,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 7 |

| Rossi et al (2005) 44 | 0 | 3 (E,F,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 6 |

| Rossi et al (2006) 45 | 0 | 3 (E,F,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 6 |

| Rossi et al (2008) 46 | 0 | 3 (E,F,H) | 3 (I,J,K) | 6 |

| von Peter et al (2002) 48 | 0 | 4 (E,F,G,H) | 2 (I,K) | 6 |

| Wells et al (2011) 39 | 3 (A,B,D) | 3 (F,G,H) | 2 (I,K) | 8 |

†Eisenberg et al, 40 Metcalfe et al, 43 Soon et al, 47 and Vukovic et al 49 do not focus solely upon CAM use for headache and migraine and, as such, the criteria “reporting of CAM use” does not apply to these 4 studies and they were not assessed via the quality scoring system mentioned.

Meanwhile, given that all previous research have utilized cross-sectional study design, there is also a need for longitudinal studies to examine changes in CAM use in accordance with changes in conventional treatments and severity of the headache disorders and throughout different stages of the headache and migraine patient’s illness and treatment journey.

While remaining mindful of cultural contexts and variations in CAM, researchers are also recommended to adopt a common taxonomy or classification of CAM practices/exposures in self-reported descriptive surveys of CAM use for headache and migraine where possible.[58] This will help address challenges resulting from rapid developments regarding evidence and institutional approvals. For example, Petasites hybridus, or butterbur root, was recently found to have level A evidence for proof of benefit in episodic migraine by the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. [20] As the evidence base demonstrates, the use and satisfaction with CAM varies among patients suffering from different kinds of headache and migraine. [49] Future research will benefit from differentiating and/or targeting patients suffering from different and specific types or severities of headache and migraine. Together, these design features will strengthen the evidence base of CAM use on this topic and provide a much better picture of CAM consumption for the treatment of headache and migraine.

Conclusion

The use of CAM appears to constitute a treatment option considered and employed by a substantial proportion of patients suffering from headache and migraine. This review has provided essential insights into the prevalence and details of CAM use and related issues among headache and migraine patients with implications for practitioners (both conventional and CAM) and health policy makers. It is recommended that further research utilizing both quantitative and qualitative methods be undertaken to address a number of important issues still requiring attention and essential to helping a range of stakeholders provide effective, safe, and responsive care and services for those suffering from headache and migraine.

References

- Adams J, ed. Researching Complementary and AlternativeMedicine. London; New York: Routledge; 2007.

- Xue CC, Zhang AL, Lin V, Da Costa C, Story DF. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: A national population-based survey. JAltern Complement Med. 2007;13:643–650.

- Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementaryand Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults andChildren: United States, 2007. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Health Interview Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD; 2008.

- Ernst E. The role of complementary and alternative medicine. BMJ. 2000;321:1133–1135.

- Harris P, Rees R. The prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use among the general population: A systematic review of the literature. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8:88–96.

- Hanssen B, Grimsgaard S, Launsoslash L, Foslashnneboslash V, Falkenberg T, Rasmussen NK. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in the Scandinavian countries. Scand J Prim HealthCare. 2005;23:57–62.

- Tovey P, Easthope G, Adams J. The Mainstreamingof Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Studiesin Social Context. London: Routledge; 2004.

- Adams J. Utilising and promoting public health and health services research in complementary and alternative medicine: The founding of NORPHCAM. Complement Ther Med. 2008;16:245–246.

- Bishop FL, Lewith GT. Who uses CAM? A narrative review of demographic characteristics and health factors associated with CAM use. Evid BasedComplement Alternat Med. 2008;7:11–28.

- Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith GT. Treat or treatment –A qualitative study analyzing patients’ use of CAM. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1700–1705.

- Adamss J, Sibbritt D, Easthope G, Young A. The profile of women who consult alternative health practitioners in Australia. Med J Aust. 2003;179:297–300.

- Conboy L, Patel S, Kaptchuk TJ, Gottlieb B, Eisenberg D, Acevedo-Garcia D. Sociodemographic determinants of the utilization of specific types of complementary and alternative medicine:An analysis based on a nationally representative survey sample. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:977–994.

- Steinsbekk A, Adams J, Sibbritt D, Jacobsen G, Johnsen R. Socio-demographic characteristics and health perceptions among male and female visitors to CAM practitioners in a total population study. Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2008;15:146–151.

- Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache:A documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:193–210.

- Natoli JL, Manack A, Dean B, et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: A systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2009;30:599–609.

- Leiper DA, Elliott AM, Hannaford PC. Experiences and perceptions of people with headache: A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7.

- Stovner LJ, Andrée C. Impact of headache in Europe:A review for the Eurolight project. J HeadachePain. 2008;9:139–146.

- Leonardi M, Raggi A, Bussone G, D’Amico D. Health-related quality of life, disability and severity of disease in patients with migraine attending to a specialty headache center. Headache. 2010;50:1576–1586.

- Couch JR. Update on chronic daily headace: Current treatment options in neurology. Curr TreatOptions Neurol. 2011;13:41–55.

- Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E. Evidence-based guideline update: Pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults. Neurology. 2012;78:1337–1345.

- Mauskop A. Complementary and alternative treatments for migraine. Drug Dev Res. 2007;68:424–427.

- Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leininger B,Triano J. Effectiveness of manual therapies:The UK evidence report. Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18:3.

- Karmody CS. Alternative therapies in the management of headache and facial pain. Otolaryngol ClinNorth Am. 2003;36:1221–1230.

- Kemper KJ, Breuner CC. Complementary, holistic, and integrative medicine: Headaches. Pediatr Rev. 2010;31:e17-e23.

- Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, Manheimer E, Vickers A,White AR. Acupuncture for tension-type headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD007587.

- Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A. Complementary and alternative approaches to the treatment of tensiontype headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12:447–450.

- Sun Y, Gan TJ. Acupuncture for the management of chronic headache: A systematic review. AnesthAnalg. 2008;107:2038–2047.

- Taylor FR. When West meets East: Is it time for headache medicine to complement “convention” with alternative practices? Headache. 2011;51:1051–1054.

- Crawford CC, Huynh MT, Kepple A, Jonas WB. Systematic assessment of the quality of research studies of conventional and alternative treatment(s) of primary headache. Pain Physician. 2009;12:461–470.

- Jacobson IG, White MR, Smith TC, et al. Selfreported health symptoms and conditions among complementary and alternative medicine users in a large military cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:613–622.

- Hendrickson D, Zollinger B, McCleary R. Determinants of the use of four categories of complementary and alternative medicine. Complement Health PractRev. 2006;11:3–26.

- Shelley BM, Sussman AL, Williams RL, Segal AR, Crabtree BF. “They don’t ask me so I don’t tell them”: Patient–clinician communication about traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:139–147.

- Shaw A, Noble A, Salisbury C, Sharp D, Thompson E, Peters TJ. Predictors of complementary therapy use among asthma patients: Results of a primary care survey. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16:155–164.

- Sidora-Arcoleo K, Yoos HL, Kitzman H, McMullen A, Anson E. Don’t ask, don’t tell: Parental nondisclosure of complementary and alternative medicine and over-the-counter medication use in children’s asthma management. J Pediatr Healthc. 2008;22:221–229.

- Thomson Reuters. Endnote X2. Carlsbad, CA: Thomson Reuters; 2008.

- Gaul C, Schmidt T, Czaja E, Eismann R, Zierz S. Attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine in chronic pain syndromes: A questionnaire-based comparison between primary headache and low back pain. BMC ComplementAltern Med. 2011;11.

- Wells RE, Phillips RS, Schachter SC, McCarthy EP. Complementary and alternative medicine use among US adults with common neurological conditions. J Neurol. 2010;257:1822–1831.

- Gaul C, Eismann R, Schmidt T, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients suffering from primary headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:1069–1078.

- Wells RE, Bertisch SM, Buettner C, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults with migraines/severe headaches. Headache. 2011;51:1087–1097.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Van Rompay MI, et al. Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: Results from a national survey. Ann InternMed. 2001;135:344–351.

- Kozak S, Gantenbein AR, Isler H, et al. Nosology and treatment of primary headache in a Swiss headache clinic. J Headache Pain. 2005;6:121–127.

- Lambert TD, Morrison KE, Edwards J, Clarke CE. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients attending aUK headache clinic. ComplementTher Med. 2010;18:128–134.

- Metcalfe A, Williams J, McChesney J, Patten SB, Jetté N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by those with a chronic disease and the general population – Results of a national population-based survey. BMC Complement AlternMed. 2010;10.

- Rossi P, Di Lorenzo G, Malpezzi MG, et al. Prevalence, pattern and predictors of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in migraine patients attending a headache clinic in Italy. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:493–506.

- Rossi P, Di Lorenzo G, Faroni J, Malpezzi MG, Cesarino F, Nappi G. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with chronic tension-type headache: Results of a headache clinic survey. Headache. 2006;46:622–631.

- Rossi P, Torelli P, Di LC, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cluster headache: Results of a multi-centre headache clinic survey. Complement Ther Med. 2008;16:220–227.

- Soon YY, Siow HC, Tan CY. Assessment of migraineurs referred to a specialist headache clinic in Singapore: Diagnosis, treatment strategies, outcomes, knowledge of migraine treatments and satisfaction. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:1122–1132.

- von Peter S, Ting W, Scrivani S, et al. Survey on the use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with headache syndromes. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:395–400.

- Vukovic V, Plavec D, Huzjan AL, Budisic M, Demarin V. Treatment of migraine and tension-type headache in Croatia. J Headache Pain. 2010;11:227–234.

- Fejer R, Kyvik KO, Hartvigsen J. The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: A systematic critical review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:834–848.

- Bishop FL, Prescott P, Chan YK, Saville J, von Elm E, Lewith GT. Prevalence of complementary medicine use in pediatric cancer: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;125:768–776.

- Bishop FL, Rea A, Lewith H, et al. Complementary medicine use by men with prostate cancer:Asystematic review of prevalence studies. Prostate CancerProstatic Dis. 2011;14:1–13.

- Russell CL. An overview of the integrative research review. Prog Transplant. 2005;15:8–13.

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:546–553.

- Taylor FR. Headache prevention with complementary and alternative medicine. Headache. 2009;49:966–968.

- Whitmarsh T. Editorial commentary: Survey on the use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with headache syndromes. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:331–332.

- Featherstone C, Godden D, Gault C, Emslie M, Took-Zozaya M. Prevalence study of concurrent use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients attending primary care services in Scotland. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1080–1082.

- Kristoffersen AE, Fønnebø V, Norheim AJ. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients: Classification criteria determine level of use. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:911–919.

Headache. 2013;53(3):459-473. © 2013 Blackwell Publishing