Kate Johnson

October 05, 2015

LAS VEGAS — In the first year after a postmenopausal women discontinues hormone therapy, her risk for cardiovascular mortality is higher than if she had continued the therapy, according to an observational study.

Hormone therapy guidelines for postmenopausal women recommend the lowest dose for the briefest period. “This has led to the clinical practice of pulling women off hormone therapy annually or biannually,” said lead author Tomi Mikkola, MD, from the Helsinki University Central Hospital in Finland.

But this study raises questions about that practice, he told Medscape Medical News.

In women 50 to 60 years of age, “we clearly see” that this “is doing more harm than benefit,” he reported. “If women are otherwise healthy, they could continue hormone therapy as long as they wish.”

Dr Mikkola presented the results, which were published simultaneously in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, during a plenary session here at the North American Menopause Society 2015 Annual Meeting. The session was partially funded by Pfizer.

Dr Mikkola and his colleagues identified 332,202 women who discontinued hormone therapy from 1992 to 2009 from two large Finnish registries: the Medicine Reimbursement Register and the Causes of Death Register. In the study cohort, mean exposure to hormone therapy was 6.2 years, and mean follow-up after discontinuation was 5.5 years.

During the study period, there were 5129 deaths related to cardiovascular issues or stroke.

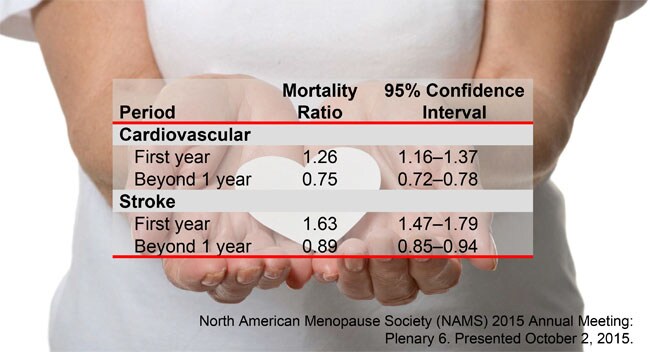

In the first year after hormone discontinuation, the risk for cardiac death was significantly higher in the discontinuers than in an age-standardized background population. However, beyond 1 year, the risk was lower.

Similarly, the risk for stroke death in the first year was higher in the discontinuers in than in an age-standardized background population.

A Paradigm Shift

In addition, cardiac mortality was higher during the first year in discontinuers than in those who continued on hormone therapy (standardized mortality ratio [SMR], 2.30; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.12 – 2.50), as was stroke mortality (SMR, 2.52; 95% CI, 2.28 – 2.77).

“In my view, we have to shift the whole attitude, first in gynecologists and general practitioners, and eventually in cardiologists,” Dr Mikkola said.

“These are irrefutably consistent data that say that hormones lower mortality — and the message is, you stop, you die,” said Howard Hodis, MD, from the atherosclerosis research unit at the University of Southern California at Los Angeles, who was not involved with the study.

“This is another piece, another step forward, that’s going to change how we look at things,” he told Medscape Medical News. “I think cardiologists will be shocked, and it will be totally resisted.”

An important limitation of this study is that compliance was measured by 3-month prescription refills. Dr Mikkola acknowledged that there is no way of knowing whether a woman filled a 3-month prescription and then discontinued treatment because of cardiovascular symptoms.

This study was funded by unrestricted grants from the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, the Emil Aaltonen Foundation, the Finnish Medical Foundation, Finska Läkaresällskapet, the Orion Farmos Research Foundation, the Paavo Nurmi Foundation, and a special governmental grant for health sciences research. Dr Mikkola and Dr Hodis have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Three of the study coauthors work for EPID Research, a company that performs financially supported studies for several pharmaceutical companies.